Wrapping my arms around myself a little more tightly, I find myself cheering on the sides of yet another cold and windy field, while I watch a group of boys emulate their soccer heroes. Their coach yells “show” or “shape” from the sidelines, while the boys put into action the moves that they’ve spent hours practicing. I watch as the V and Cruyff drills come pouring out onto the field, and succeed as they were intended.

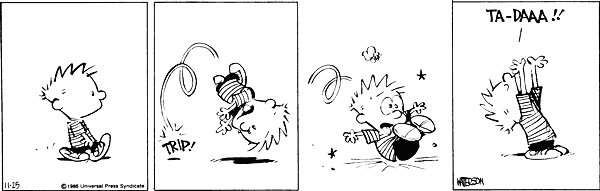

I also watch as one boy attempts a back pass that fails, spectacularly, sending the ball directly to an opposing player and nearly costing a goal. On the sidelines, we parents hold our breaths for a beat, before the game goes on. And we all watch, as not two-minutes later, another boy tries the same move. It too, falls flat, but this time, there is no audible reaction from the sideline.

Instead, we chat about the first few weeks of school, and how our boys are growing before our eyes, now within spitting distance of adolescence. A comment is made about the crazy back pass move, and how the coach encourages the boys to use everything he teaches them on the practice field in games, even if they fail, even if they lose. It’s a new refrain in a competitive sport environment, and certainly not the first time this idea has presented itself.

It seems clear that our attitudes towards failure are shifting. Certainly, my scholastic and sports careers had very different takes on failure. Essentially, it amounted to do it well, or don’t do it at all. I have vivid memories of my high school soccer coach screeching and goading us from the sidelines. He went out if his way to chastise failures or stubbornly benched those whose performance he judged wanting, maintaining that it was the best way to motivate us to improve. As a youth referee, I also heard parents scream that under-performing kids should be pulled off the field. The idea of actually embracing failure would have been a colossal faux-pas in their eyes.

The concept of allowing for failure though is percolating everywhere these days. As a parent, I’ve heard similar mantras in the schools, at least here in Ontario. One term that keeps floating around is ‘growth mindset’ – effectively a principle that stands in direct contrast to a traditional understanding of failure. The idea is attributed to psychology professor, Carol Dweck, who postulated that our minds are dynamic, ever changing and capable of growth. Failure, therefore, is just another avenue for learning. The corollary to this is ‘fixed mindset’, which assumes that character and abilities are fixed, and failure is an indication when an individual has exceeded their potential.

So, what’s changed? Certainly, the definition of failure remains the same – a lack of success in an endeavour. It seems, though, that a broader philosophy of failure is emerging. And like many of the cultural influences we experience these days, I can’t help but look to the technology sector as a prime influencer.

In a recent TED Talk, Astro Teller, the head of R&D for X (formerly Google X) – the somewhat secretive lab at Google whose mission is to develop far-reaching, and somewhat crazy projects into reality – explained how the company had embraced the benefits of failure. At X, project teams received bonus’ and accolades when they successfully identified a fatal flaw and canceled their own project. In fact, they were challenged to start with the hardest parts first with the aim of determining as early as possible whether the project was going to ultimately be attainable. The idea, Teller noted, was to create an environment where employees felt safe to take risks and bring forward, what he called, moonshots – crazy solutions to difficult problems.

And X is far from the only company whose ethos is embracing the ideology of soft landings for pushing the envelop on ideas. A quick internet search gives lists of companies, both in and outside of high tech, that have some sort of reward or celebration for failure. Publicly at least, a growing number of companies are ascribing to the idea that great ideas come through failure. But it is the high tech companies, those who seem to push the envelope the widest on innovation, who seem to truly lead on the celebration of failures.

So, the question becomes, has this philosophy of failure seeped its way into the broader culture? Companies like Apple and Microsoft, where the failures that pre-dated these successes have acquired mythic status on their way to sector domination. And it’s undeniable, that every aspect of our daily life is now influenced in some way by technology. Computers, phones, gadgets – they permeate every aspect of our lives.

What’s more, work culture has been highly influenced, not only by technological innovations, but by work approaches and systems pioneered in technology workplaces. Think open concept offices, flexible work hours, paperless files, just to name a few. Is it such a stretch that our approach to education is now under similar influences?

When my kid came home last year with a failed math test, I was torn about how to address it. He, however, didn’t seem to be concerned at all. But, I was worried. Did I need to bring down the hammer? Should I make him do extra math work? Do I pull out the “importance of studying” lecture? Or do I let it slide, seeking to prioritize his confidence over a grade on a single test?

Before I could decide any of this though, my kid settled the issue for me.

“Mr. Smith says I don’t have it yet, but I can do a re-test next week. I know where I made the mistakes now, so I’ll do better,” he casually stated while grabbing for a snack in the fridge.

And that was that. Failure in action.

It remains to be seen in the long run whether this new philosophy of failure will prevail, and whether it will indeed be better for our kids’ education. But for the moment, I have to say, it seems a far healthier attitude than that of my high school soccer coach.

In an ironic twist, our reliance on digital devices to keep our kids safe and connected to us, may be hurting them.

In an ironic twist, our reliance on digital devices to keep our kids safe and connected to us, may be hurting them. health, we keep buying them for our kids. According to data gathered by MediaSmarts, nearly three quarters of 14 and 15 year-olds in Canada have their own device.

health, we keep buying them for our kids. According to data gathered by MediaSmarts, nearly three quarters of 14 and 15 year-olds in Canada have their own device.